A Crisis in Battle Rap

How can battle rap culture persevere after COVID?

Battle rap is experiencing an unprecedented crisis since it first gained popularity with the rise of online video platforms. By analyzing a data set of over 10,000 rap battles, I have identified patterns which allow league owners to determine battle match ups quantitatively, taking into account current trends and areas of growth within the culture.

# A Brief History of Rap Battling

Rap music has always had a competitive dimension, and there are many examples of feuds between rappers being carried out on ‘dis-tracks’. However, rapping as a lyrical exercise has also been applied to non-musical competition, where two opponents face off against each other in front of an audience with no musical accompaniment.

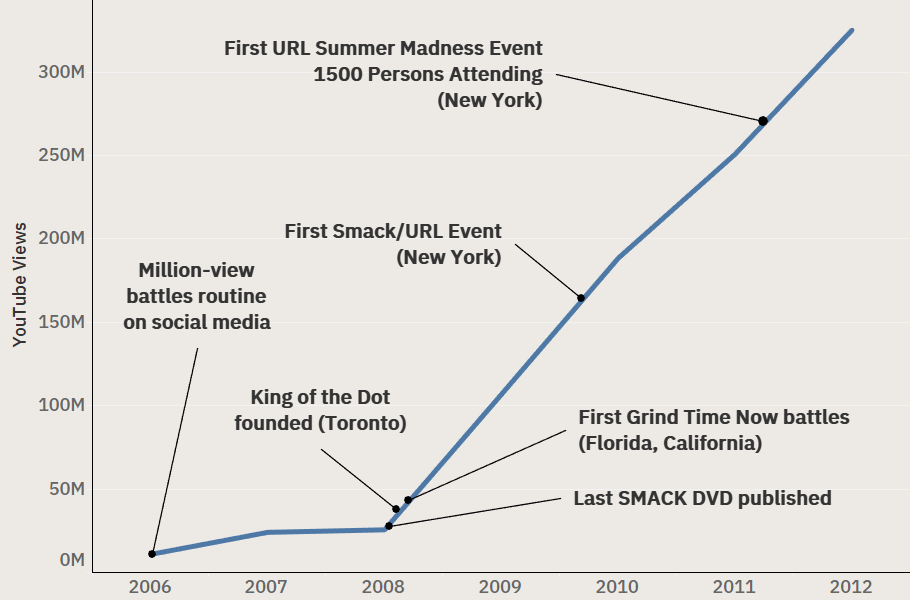

In the early 2000s, a series of DVDs called “SMACK” was published, featuring battles filmed in front of small audiences on street corners and in record stores. By the mid 2000’s these battles had made their way onto social media, and eventually a common format for the battles became standardized – two opponents facing each other with both improvised and written lyrics, in a series of three three-minute rounds. The result of the battle is rarely judged formally – the audience is left free to discuss and argue about the winners and losers.

As the decade progressed, the audiences grew to fill major venues, and the popularity of the movement spread worldwide, with different battle rap leagues developing their own talent.

With the increased viewership and revenue, battle rap flourished creatively, with a wide range of styles and rhetorical strategies being used to win over an audience. The lyrical content of battle rap is often violent and obscene, but also jovial and funny. Unlike some notorious mainstream feuds between rappers, battle rap events have never seen serious violence.

# A Crisis in Battle Rap

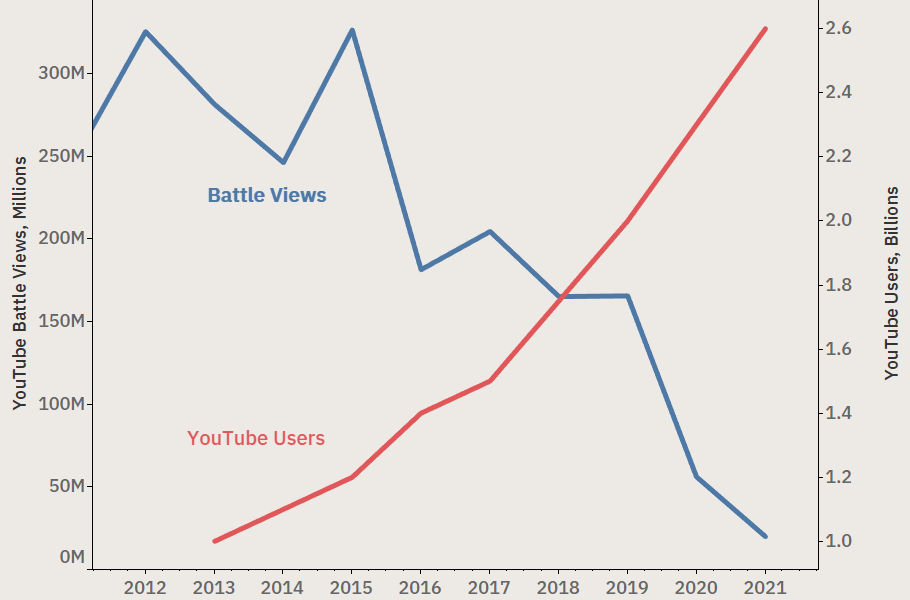

Any fan will tell you that battle rap isn’t doing well in 2021. COVID lead to cancelled events, and the battles that did occur took place in small venues with smaller crowds, lacking the excitement of the big events of the past.

However, examining the popularity of battles released since about 2013, we can see a steady decline, despite the fact that YouTube use increased dramatically. Assuming a nominal value of $4 per 1000 video impressions, the revenue seen by battle rap leagues has fallen from around $1.3M/year to less than $250K at present.

YouTube is not the only income seen by the leagues – tickets to battle rap events are often around $100. At a large venue, like Webster Hall in New York, ticket sales could easily top $140,000 for a single night.

Nevertheless, the shrinking YouTube viewership should be worrying to leagues not just because it reflects diminished revenue, but because the video platform has historically been the best way to reach new fans, who will attend events, buy sponsored products, or be inspired to participate in the battles themselves.

# Engagement Now and Future

The purpose of this piece is to explore how battle rap leagues can engage and grow their audience in the future. The fundamental method that leagues use to drive interest in battles is the match up: choosing who will battle whom.

Since rap battles are not formally judged, choosing the winner is subjective. In contrast, popularity – as measured by Twitter followers and YouTube impressions, is not.

Traditionally, leagues choose battlers by finding two performers who think they can win against each other. Since rap battles are not formally judged, choosing the winner is subjective. In contrast, popularity – as measured by Twitter followers and YouTube impressions, is not. As a result, the ability of a battler to create interest around his or her name is one of the best ways to measure their success.

I have examined a data set of over 10,000 rap battles on YouTube, and have created a set of recommended match ups which reflect both tried-and-true methods for driving engagement, as well as new opportunities to capitalize on growing trends.

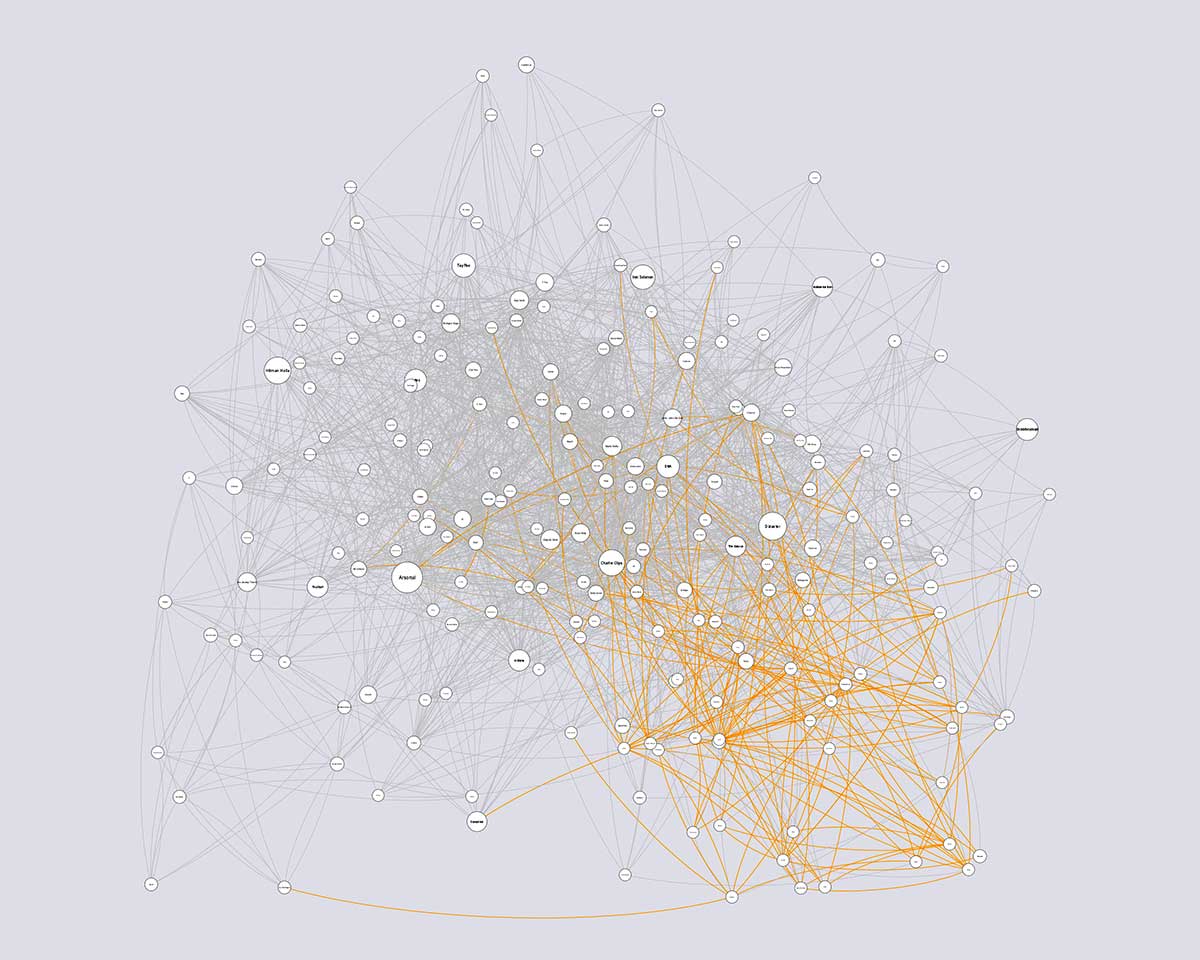

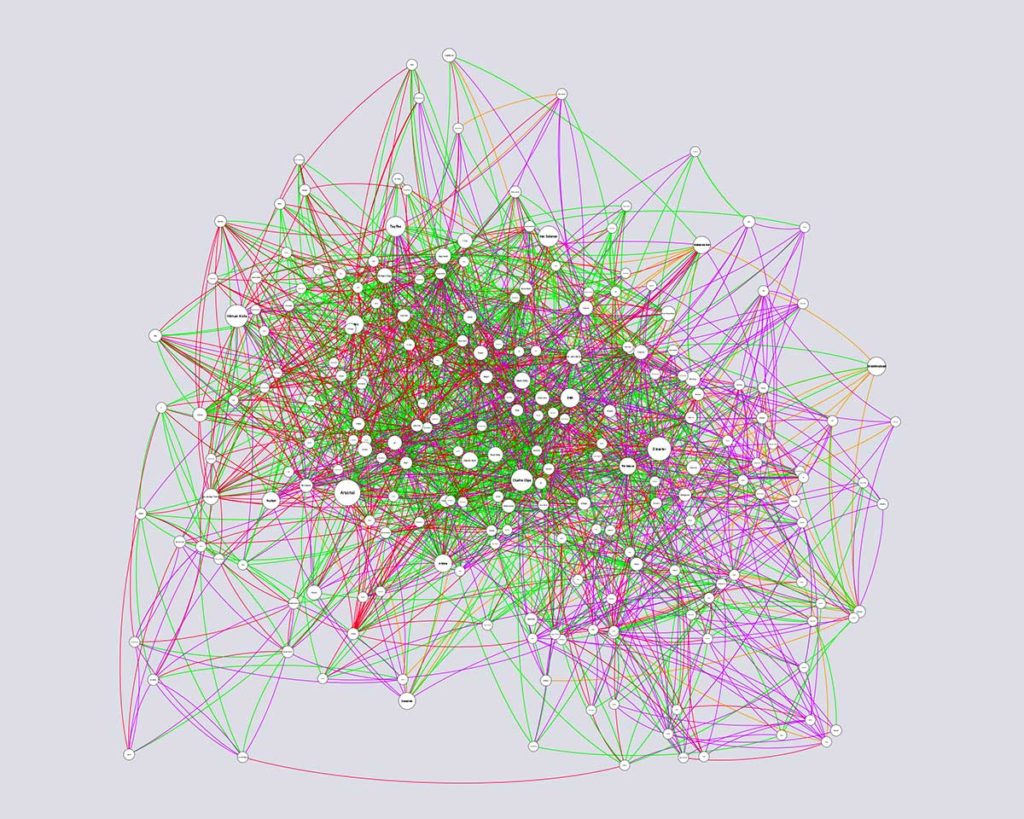

# Battle Rap as a Social Network

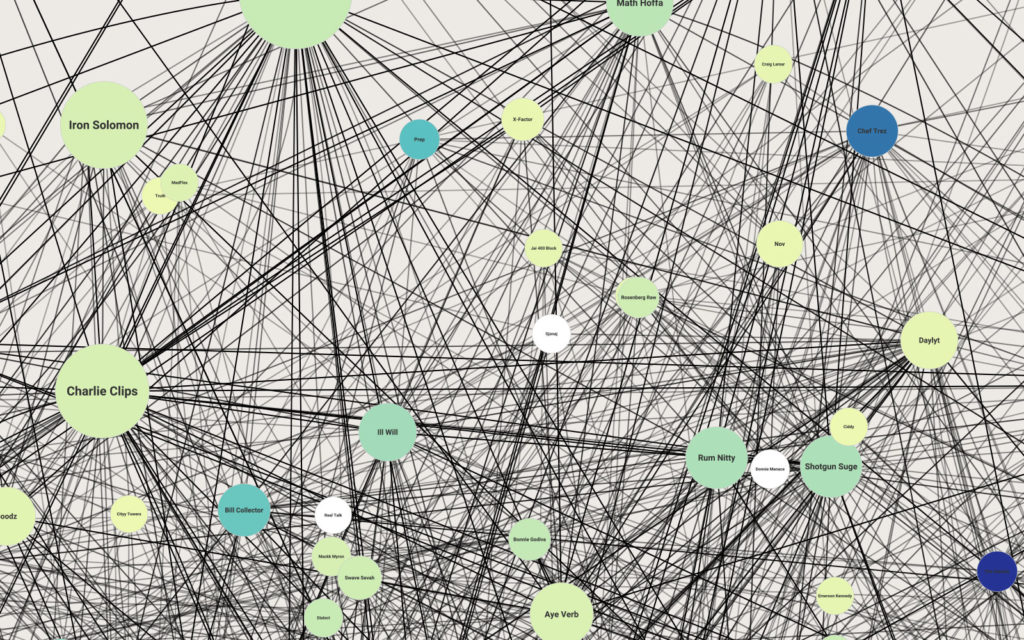

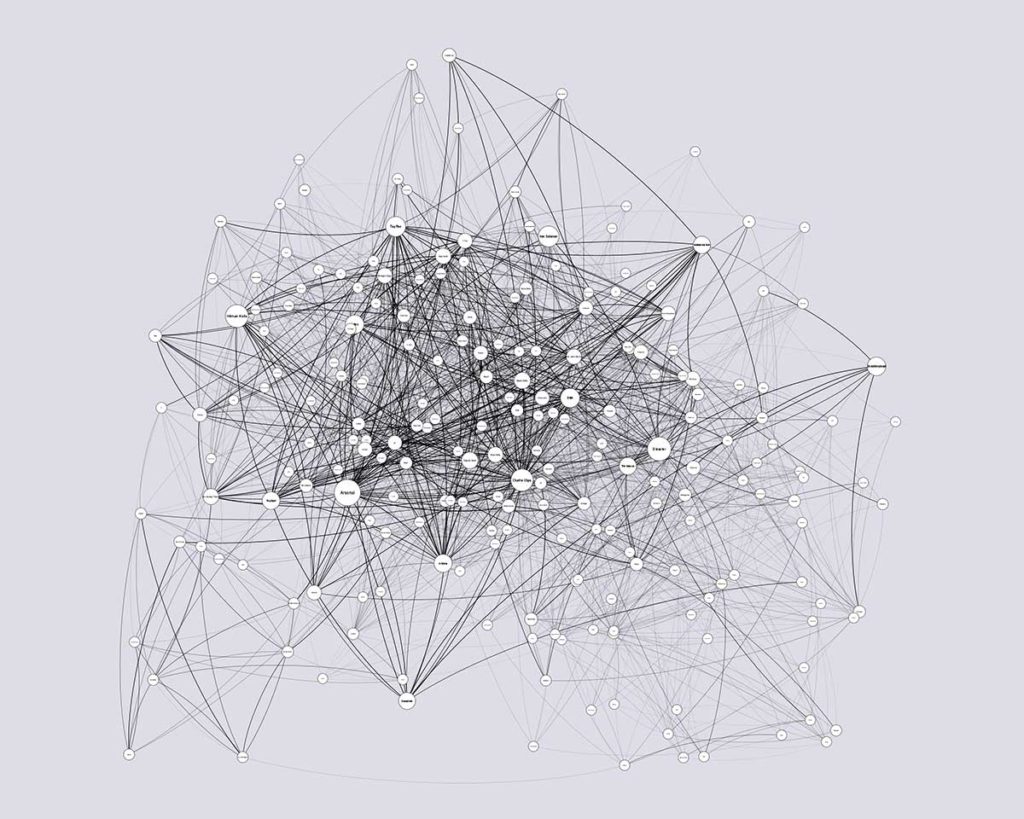

Using network visualization software, I created a network of all battle rappers from 2006-2021 with 3 or more battles. Each node is an individual battler, and each line is a battle. The size of the node corresponds to an era-adjusted total of YouTube views, with eras having fewer total views being awarded greater weight to account for the relative prominence of these battles.

It’s clear that the battle rap world is highly connected. The nodes are organized by proximity – groups of battlers near each other are more likely to have battled each other. Despite this, there are lines (battles) crossing the entire graph. Let’s see what actually defines the different communities in battle rap.

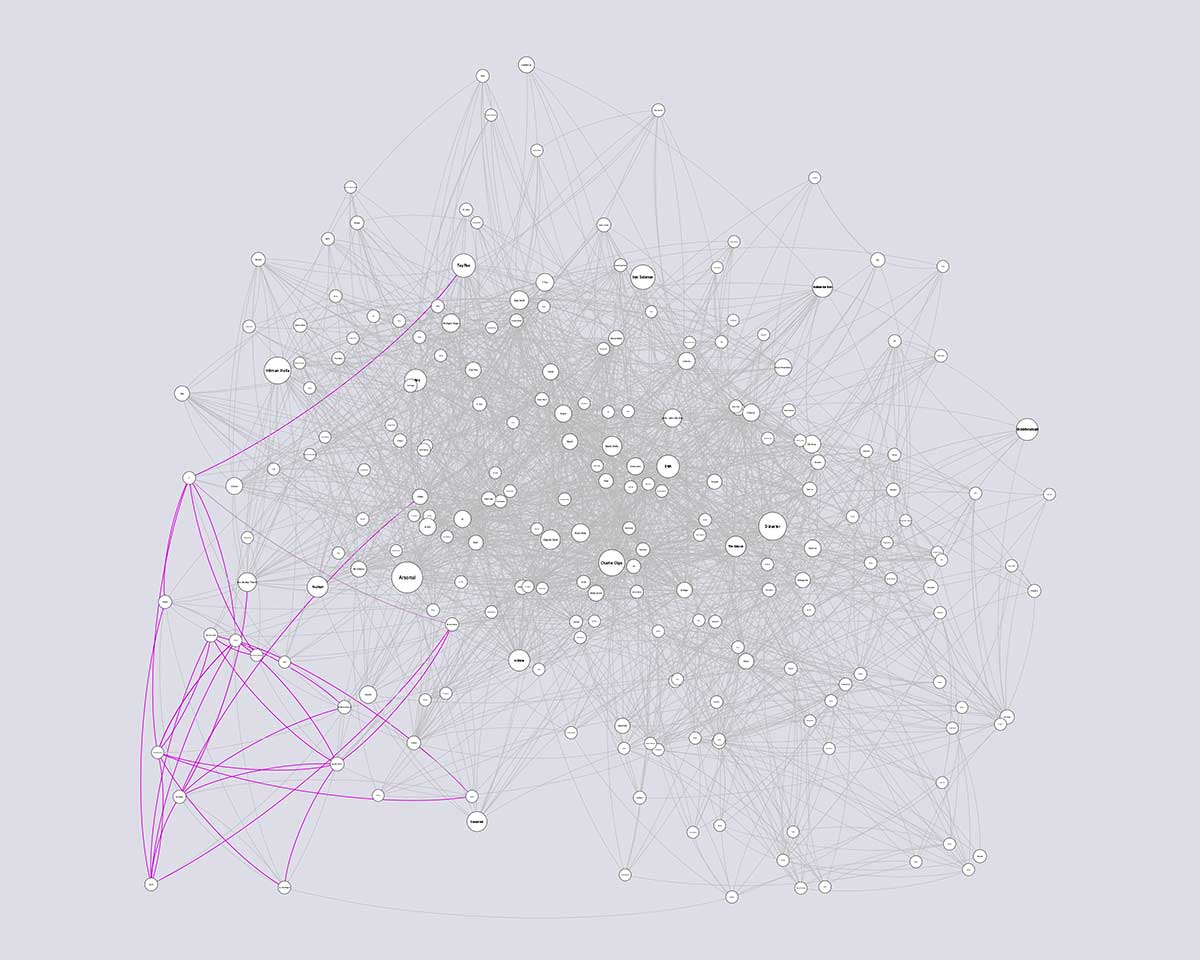

Organized by Era:

In this image, the line colors (green, orange, magenta and red) correspond to battles occurring in different 4 year eras, starting in 2006. It is clear that there is some of each color in almost every area of the graph, meaning that the battler proximity does not correspond to different eras very well. This makes sense, as popular battle rappers can have long careers, enabling them to compete against all eras. Loaded Lux and The Saurus, who were both competing by 2006, still compete today.

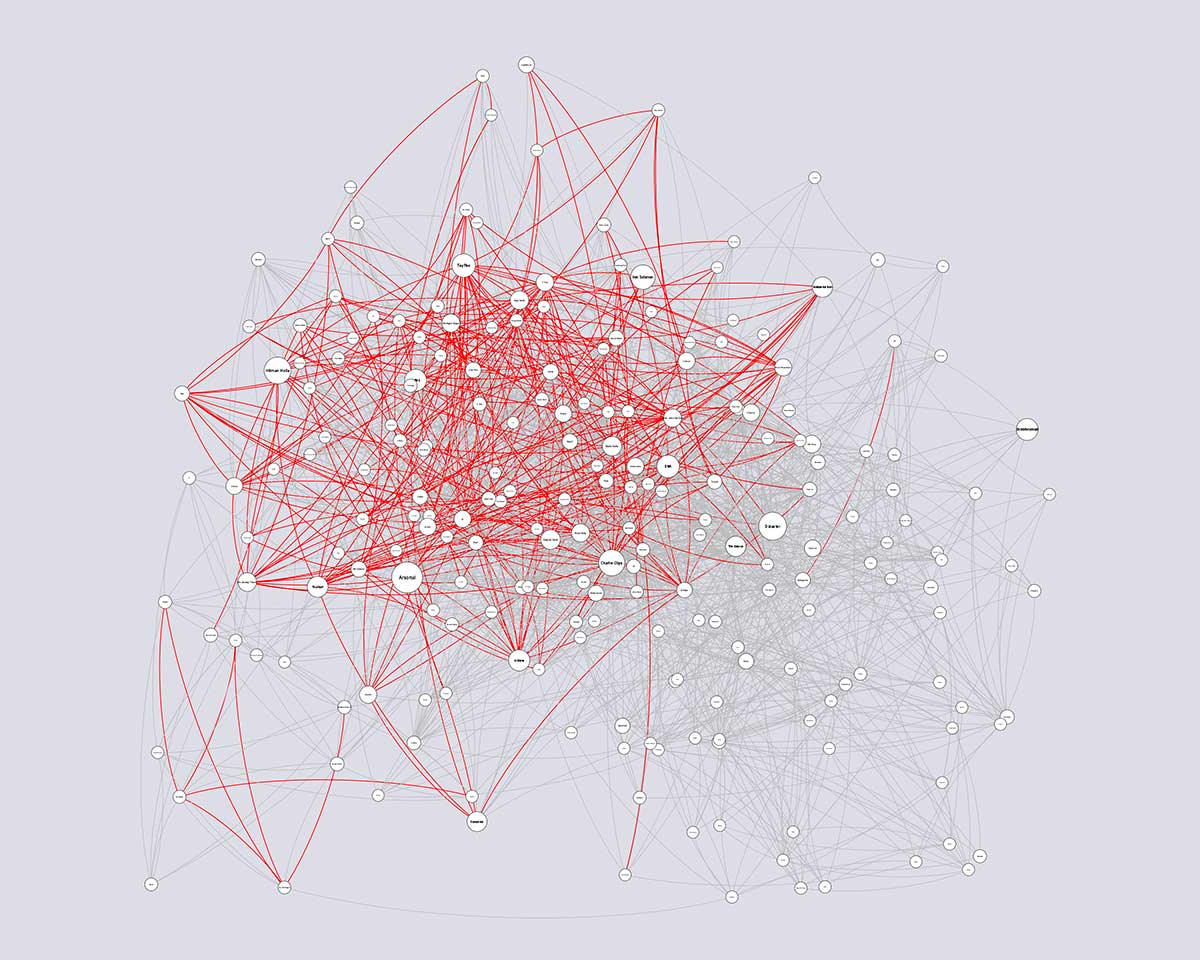

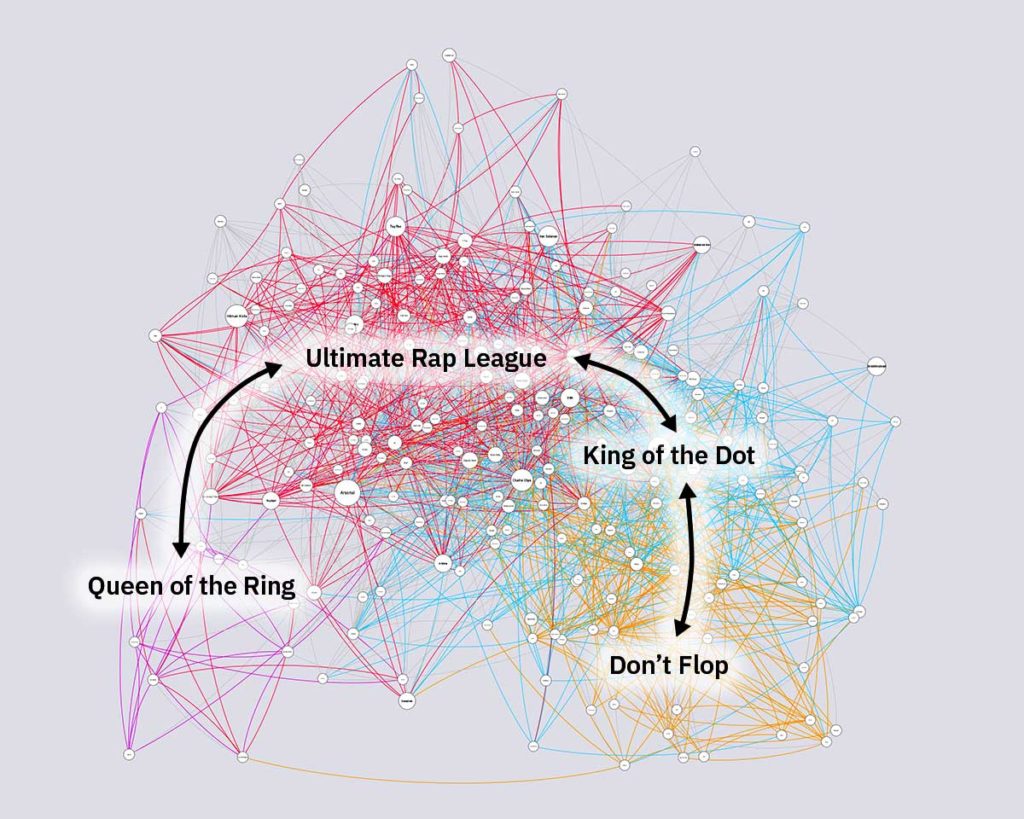

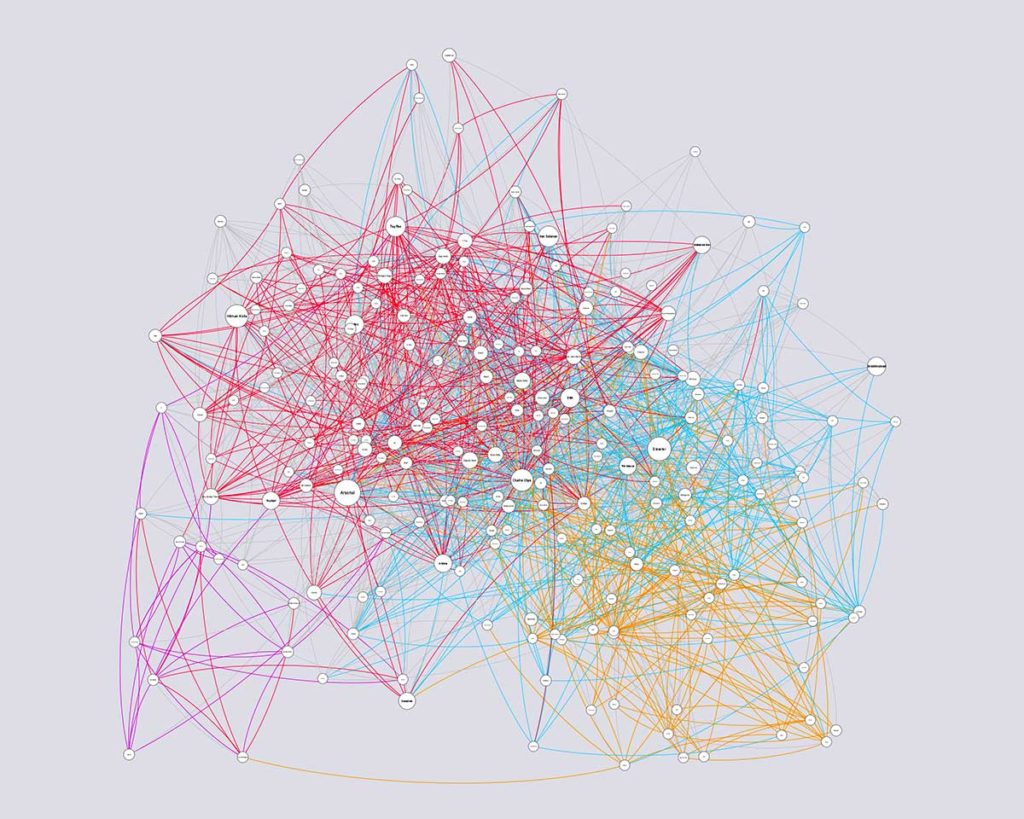

Organized by League:

In these images, battles are colored according to which league they belong to. I colored the five most prominent leagues in recent history to show that it is the leagues which have traditionally defined battle rap.

- Ultimate Rap League (URL) is the biggest league, based in New York

- Rare Breed Entertainment (RBE) is also based in New York

- Don’t Flop is the largest league outside the U.S., based in the U.K.

- Queen of the Ring is an offshoot of URL, featuring female battlers

- King of the Dot (KOTD) is a large league based in Canada

# Generating High-Interest Battles

I suggest two approaches for generating high-interest match ups. The first is similar to how leagues have traditionally operated – keeping to their own talent pool and developing the best match ups within it. The second is what I call the bridge method.

Building Bridges:

If we look at the following diagram of rap leagues, we can see that some are more connected than others:

We can see in the lower left that Queen of the Ring is strongly connected to the Ultimate Rap League but only barely connected to other leagues. Similarly, the Ultimate Rap League is strongly connected to Queen of the Ring and King of the Dot, but is not well connected to the other two leagues. King of the Dot is probably the most expansive of all leagues, but is mostly connected to Ultimate Rap League and Don’t Flop.

In a sense, the whole contemporary landscape of battle rap can be characterized as a line connecting Queen of the Ring ↔ Ultimate Rap League ↔ King of the Dot ↔ Don’t Flop.

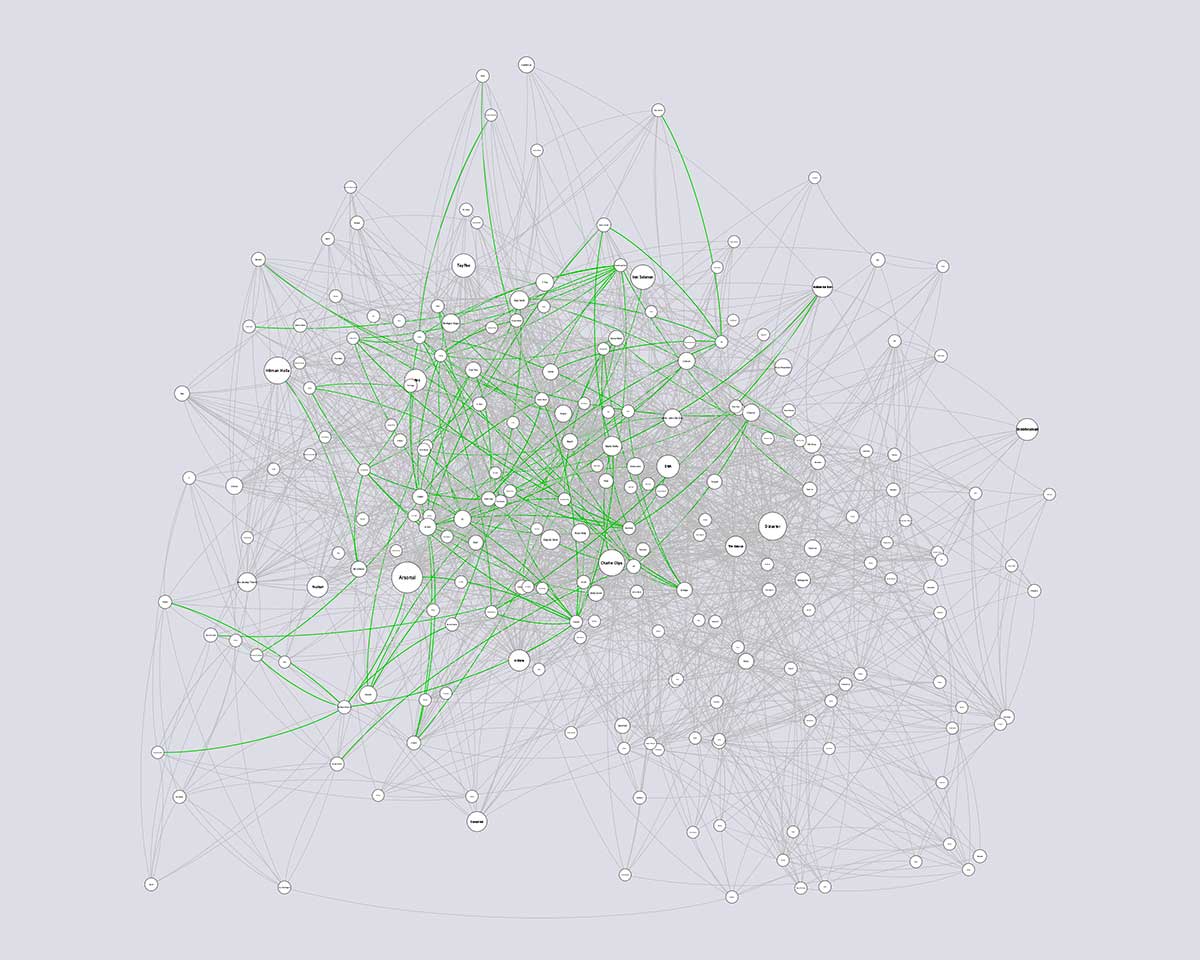

The success of RBE:

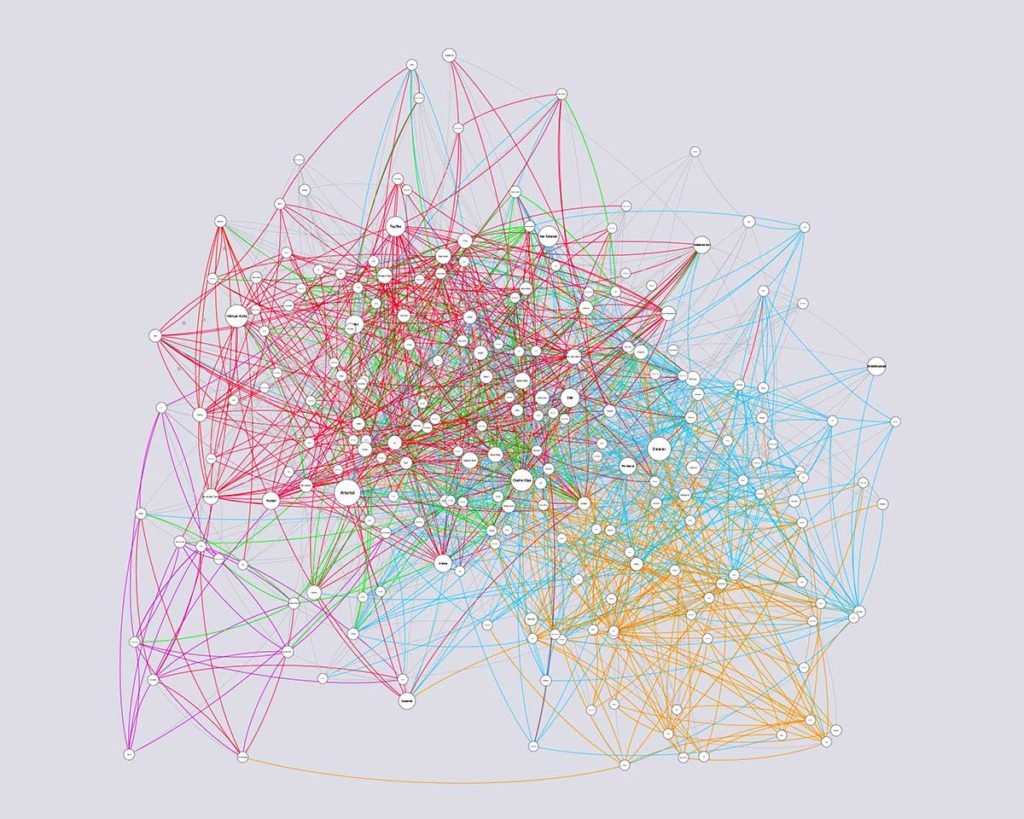

Observant battle rap fans may notice that one league has been left out of this analysis: Rare Breed Entertainment (RBE). RBE is one of the fastest growing leagues in battle rap culture, having grown to #2 in YouTube views despite only having started in 2013. I believe the following image illustrates part of the reason for their success:

Major Rap Leagues (No RBE)

Major Rap Leagues (RBE = Green)

On the right, you can see the map of battle rap leagues I have shown before. On the right, RBE has been added. It’s barely visible! RBE, despite being a large league, has a very diverse range of talent which it draws from. Its talent pool is intimately mingled with URL, but relatively well connected to the other major leagues as well.

RBE, having started relatively late, does not have the iconic, marquee talents associated with it the same way other leagues do. However, they have recognized that great battle rap match ups can be drawn from the whole talent pool of battle rap, and are able to put on battles which are driven by diverse interests, rather than the regional interests represented by the older leagues.

# A View to the Future

I believe that for battle rap culture to have a bright future, the match ups need to combine the techniques of traditional match up promotion with promotion based on a broader, quantitative approach.

Traditional matchmaking uses two rappers from the same city – or neighborhood, and harnesses their familiarity to make for entertaining and personal battles. This is the model used by leagues like the URL, who actually develop talent in a sort of minor-league system, and where battlers are sometimes compelled to compete only in their league.

Quantitative matchmaking uses a broader view of appeal to determine the rappers that people all over the world want to see, and combine them accordingly.

The match ups I suggest use what I call the bridge method, where novel, high value match ups are found in adjacent battle rap leagues. The advantage of choosing from adjacent battle rap leagues is that since they are already somewhat connected, there is enough familiarity for the opponents to have relationships to draw on as they compose their rounds. At the same time, battlers associated with different leagues are likely to represent different styles, regions, and peer groups, allowing for a differences to be highlighted in battles.

# Suggested Battles

The process for generating high interest match-ups is not complicated. First, a list of the current top 10 battlers from each league is prepared. I have also included the top 10 battlers from all leagues, to catch battlers not tied to one league:

| QOTR | URL | KOTD | Don’t Flop | All Leagues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ms Fit | Cassidy | Oxxxymiron | Shox The Rebel | Oxxxymiron |

| P. Funeral | Goodz | Dizaster | Soul | Dizaster |

| N. J. Twork | Tay Roc | Cortez | Tony D | Cassidy |

| Ms Hustle | Chess | Daylyt | Arsonal | Goodz |

| 40 BARRS | Hitman Holla | Danny Myers | Chilla Jones | Hitman Holla |

| Couture | K-Shine | Hollow da Don | Charron | Tay Roc |

| O’fficial | Hollow da Don | Serius Jones | Harry Baker | Chess |

| Tori Doe | Arsonal | Pat Stay | Charlie Clips | K-Shine |

| Chess | Brizz Rawsteen | Bigg K | Raptor Warhurst | Hollow da Don |

| Casey Jay | Geechi Gotti | Arsonal | Dialect | Bill Collector |

These lists are loaded into a miniature database which then creates lists of all possible match ups according to different criteria:

Adjacent Leagues:

Queen of the Ring ✕ Ultimate Rap League

Ultimate Rap League ✕ King of the Dot

King of the Dot ✕ Don’t Flop

Top Performers Within Leagues:

Queen of the Ring ✕ Queen of the Ring

Ultimate Rap League ✕ Ultimate Rap League

King of the Dot ✕ King of the Dot

Don’t Flop ✕ Don’t Flop

Top Performers , All Leagues:

Top 10 All Leagues ✕ Top 10 All Leagues

Filtering the results:

After filtering out battles that already have occurred, we are left with 335 battles.

I then sorted the data by the combined popularity of the match up – all things being equal, two very popular battlers will generate more interest than two who are less popular.

Here are the top 150 by this criteria:

Top 150 Matchups

There are a number of ways to filter this data – one, by examining the difference in average views for each battler, you can spot match-ups that may be somewhat lopsided. On the other hand, there is a tradition in battle rap of established battlers facing off against new talent, providing the excitement of either a resounding defeat, or a surprising upset.

Another thing you will notice is that certain names pop up a lot. This is because, apart from some battlers simply being very popular, there are some battlers who are on the top 10 list of more than one league. Arsonal, Cassidy, Chess, Dizaster, Goodz, Hitman Holla, Hollow da Don, K-Shine, Oxxxymiron and Tay Roc are all battlers who have created a reputation which surpasses a single league, and should be the first names to look at for exciting match-ups.

Caveats:

Choosing opponents for a rap battle is a creative act, and it cannot be reduced to a numerical exercise. The success of a battle rap league is to a great degree dependent on the skill of the match making and marketing. Battle rap history is full of examples of ‘big name’ battles which failed to impress, and battles between no-name battlers which became part of battle rap history.

However, it is clear from my analysis that rap leagues need to look to the example of highly connected leagues like RBE to expand interest in their product. Some leagues, such as URL and KOTD, have already exhausted many of their own top match ups, indicating that new match up strategies are needed. I believe that the method of using adjacent clusters of battlers is an effective one to find unexpected and potentially exciting match ups.

One of the greatest benefits from using an analytical mindset to examine an entertainment product is that it shows how your own personal tastes effect your perception of a whole culture. I’ve been watching battle rap since 2007, and this exercise showed how little I know about the breadth of battle rap, or what is truly popular on a global basis.

# Addendum: Tools and Data Sources

All the data for this project was scraped from Versetracker.

The graphs showing league popularity were generated with Tableau.

The network diagrams were generated using Cytoscape.

Data on YouTube viewership was found here.

Data was processed with Excel and MySQL

If you would like to view the entire battle rap network image, I have uploaded it to easyzoom. You can view it here.