Job Satisfaction in Architecture

Researching the ingredients for happy employees and happy architectural practices.

Starting in 2017, I began interviewing architects about their careers for a thesis project documenting the factors impacting their desire to stay at a firm as staff, and the difficulties they experience as managers trying to find and retain the right people.

# The right people, the right place

“At times, the hiring process, from both sides of the table, can seem like an exercise in deception. Firms will paint a rosy picture about the nature of the work and the opportunities it comes with, and applicants will paint a rosy picture of their work ethic and loyalty. I do not believe this has to be the case.”

At the time of this project, one of the dominant trends in the industry was the polarization of firm sizes, with an estimated 78% of firms considering mergers and acquisitions1. With these acquisitions, more architects will find themselves working for a smaller number of ever-larger firms. When I read about this, it struck me that this reduces choice for employees who may prefer working at smaller practices, and creates problems for people trying to staff larger practices, who have to attract employees who might not like working in a bigger, more corporate environment.

Other major changes in the industry include the rapid embrace of BIM (a standard for younger staff, still a mystery to some management) the use of professional social media (allowing architects to move between jobs more easily), and of course COVID. All these changes represent challenges to the ever larger architectural practices trying to compete.

What has not changed is that architects need to find a place where they will be happy, and architectural firms need to find the people who will be happy working for them.

# Method of Inquiry

My method for finding out what makes architects happy started by conducting a series of informal interviews. I asked them about their careers, their accomplishments, their disappointments, and what they thought of the current state of the industry.

These interviews revealed a common set of themes, which I used to develop a formal questionnaire which I would then use to characterize the culture at five large Boston-area firms.

Since I was interviewing both junior staff and senior managers, some questions have two variations depending on the interviewee. I have marked these question variations as J: for junior and S: for senior.

- S: What is the most important quality for an applicant to have?

J: Were you hired for a specific task? Are you still doing that thing? - S: When doing long term staff planning, do you ask staff about their preferences?

J: What does the firm do to develop staff, and has it been successful? - S: Apart from creating contract documents, what does your firm do with BIM models?

J: Do you feel the firm is technologically advanced compared to other firms? - Are you able to work from home?

- How, and in what way are principals involved in project management?

- Do you see yourself one day being a principal at this firm?

- What is the most unique thing your firm offers clients?

- How is the firm organized spatially?

- S: What are the common reasons younger staff leave the firm?

J: What would the firm have to do to keep you on for six more years? - What challenges to women face at your firm?

- S: If you have children, how did your attitude towards work, and your role, change?

J: If you were to have children, how would you expect your attitude towards work, and your role change? - About how many hours do you work in a week? Do you feel you need to work a certain number of hours to advance in the firm?

At each firm, I spoke to one junior staff member and one manager. In each case, the junior staff member was either right out of school or still in graduate school. The managers were more experienced, and responsible for hiring decisions. By interviewing both junior and senior staff at the same firms, I could not only understand the issues which mattered to both of them, but see the degree to which they were on the same page about the nature of the firm they represented.

# Structured Interview Results

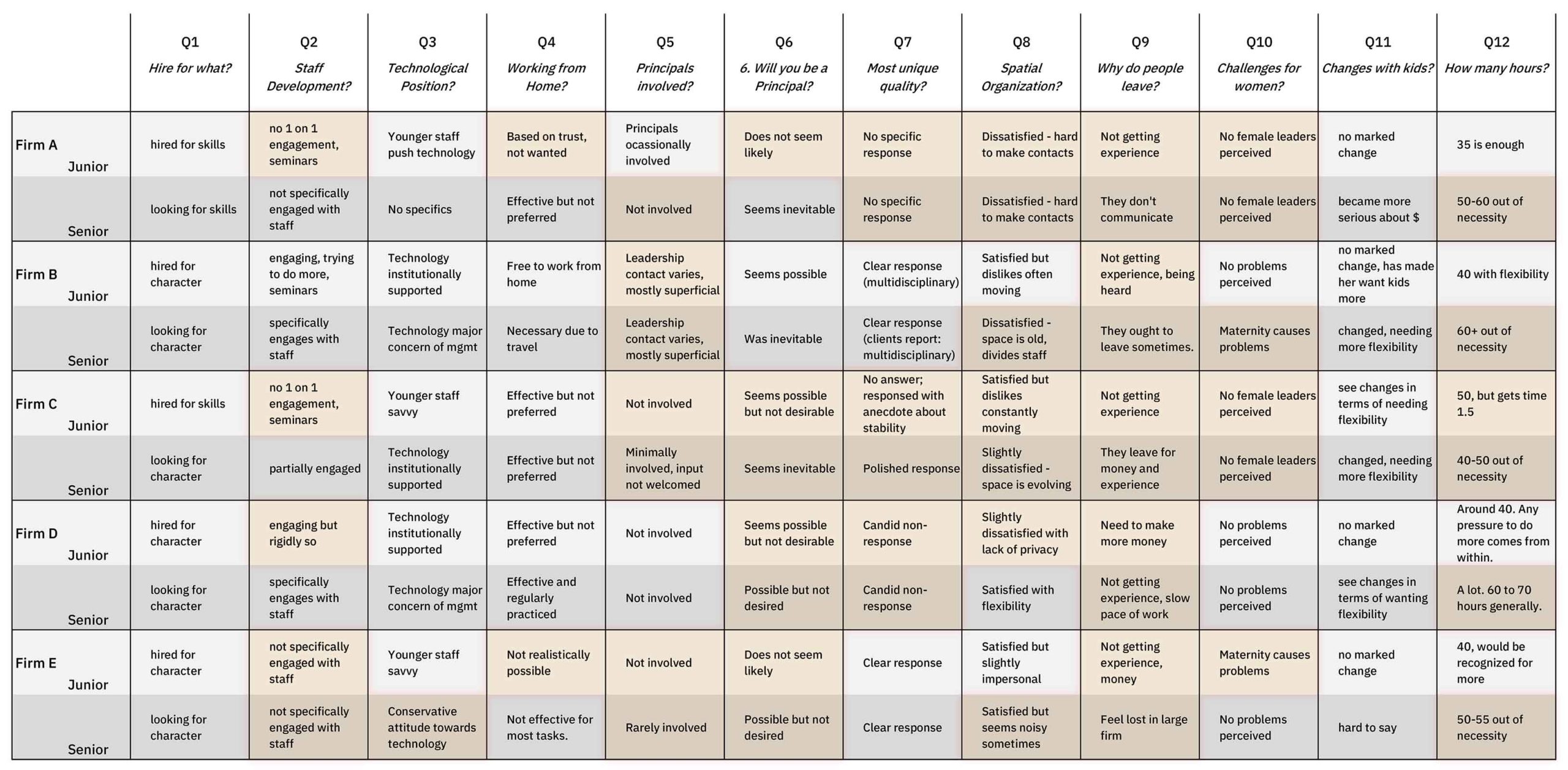

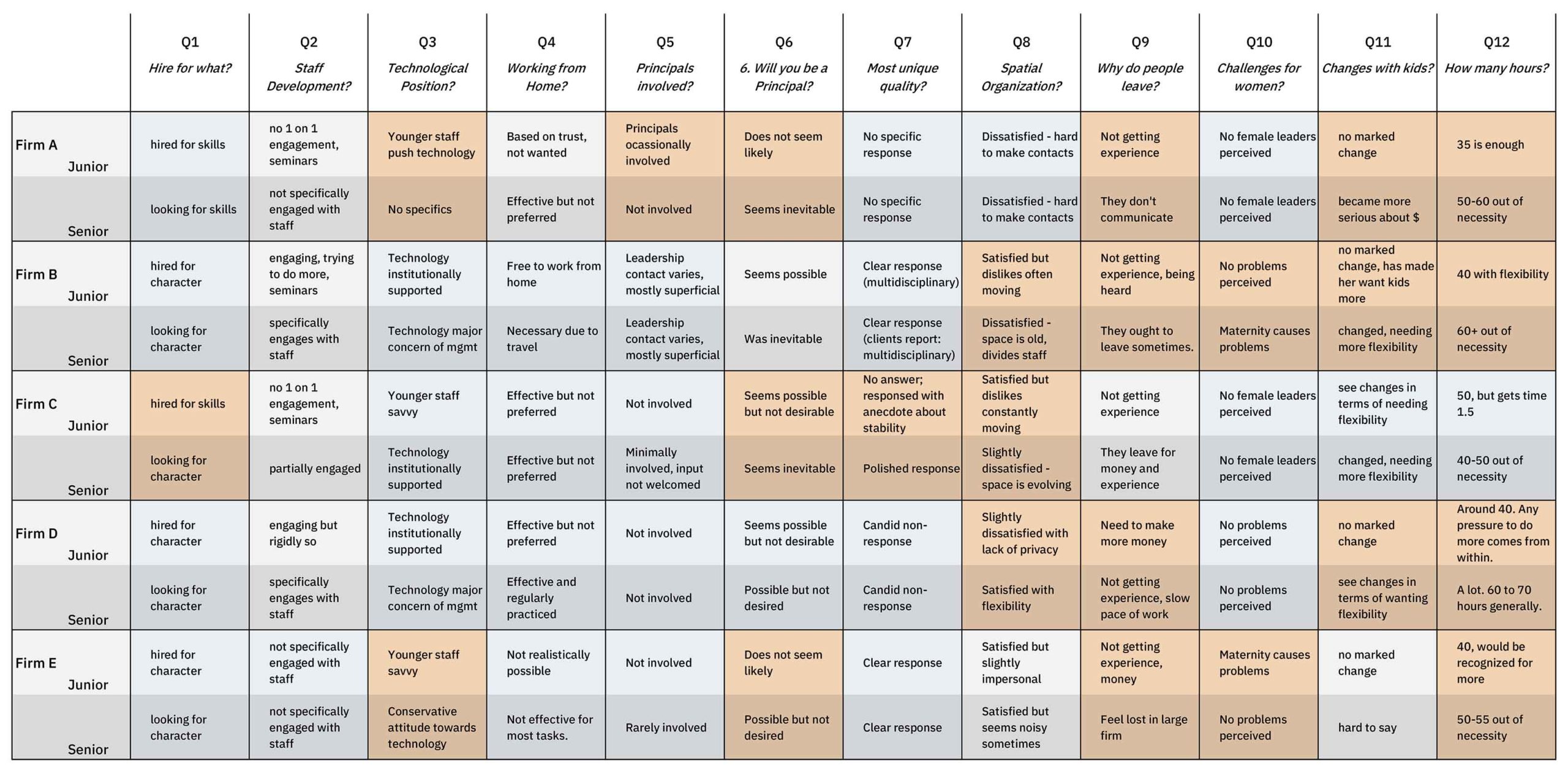

The following image is a table summarizing my interview responses to the 12 questions. In each case, the Junior employee’s response is above the response of a firm manager.

Tabulating the results:

The following table counts the number of concerning statements or grievances for each question asked during the interviews:

| Issue: | Junior | Senior | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hired for what? | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Staff development | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 3. Technological | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Work from home | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 5. Principal involvement | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 6. Leadership track | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 7. Firm identity | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 8. Office layout | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 9. Why people leave | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| 10. Challenges for Women | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 11. Changes with kids | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. How many hours? | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Total Grievances: | 32 | 29 | 61 |

My data clearly shows some questions are more contentious than others. It also shows that in general, junior staff and senior staff seem to report problems at around the same rate.

Some comment are warranted to generalize the grievances mentioned in response to these questions.

5. Principal involvement?

In most cases, the problem mentioned is the lack of principal involvement in the day to day work of the interviewee. For junior staff, this might be unsurprising, but for firm managers to have limited contact with principals points to an issue with the direction of the firm.

6. Leadership Track?

In many cases, both junior and senior employees say they do not find the idea of becoming a principal appealing. What does this say about their long term goals with the firm? These responses indicated to me that there is a major cultural divide from firm leadership and firm staff, with the latter seeing neither the appeal or possibility of joining the former.

7. Firm Identity?

This is somewhat of a trick question – the goal is not to determine what is the most unique quality possessed by a given firm, but to see if interviewees can respond in a confident manner, citing something which differentiates their firm from others. Do they truly see their firm as exceptional, or just one of many service providers? In many cases, interviewees could not proffer any real statement as to the unique value of the firm they work for.

8. Office Layout?

Many people had complaints about office layout. Complaints ranged from staff being divided, displeasure about frequent workspace moves, and displeasure with privacy and noise levels. These complaints were generally shared between junior and senior staff.

9. Why do people leave?

It should come as no surprise that the reasons why people leave a firm should be concerning to a firm. Nonetheless, it is useful to see that there is some consciousness of the fact that people leave because they aren’t getting work experience they want – or in some cases, need for licensure. Compensation is also cited as a major reason for departure.

12. How many hours?

Generally, junior employees report reasonable hourly commitments, but in each case, senior staff reported routinely working more than 40 hours a week. One senior interviewee reported 60-70 hours regularly.

Although I believe that these responses denote problems with the firm in question, this may not hold true for all people. Some people may have no problem working long hours, or may disdain input from principals, or not want to rely on their firm for professional development.

Different firms have different cultures, some more demanding, some less personal. There is nothing wrong with that, as long as nobody feels deceived. By tabulating the areas of disagreement, we can see the issues that typify differences between junior and senior staff members, with the hopes of improving communication.

Are junior and senior staff on the same page?

| Issue: | # Disagreements |

|---|---|

| 1. Hired for what? | 1 |

| 2. Staff development | 0 |

| 3. Technological | 2 |

| 4. Work from home | 0 |

| 5. Principal involvement | 1 |

| 6. Leadership track | 3 |

| 7. Firm identity | 1 |

| 8. Office layout | 3 |

| 9. Why people leave | 4 |

| 10. Challenges for Women | 2 |

| 11. Changes with kids | 3 |

| 12. How many hours? | 4 |

| Total Grievances: | 24 (40%) |

According to my assessment, on a full 40% of the assessed issues, there is disagreement in responses between junior and senior staff members. Some questions showed clear trends towards greater disagreement between junior and senior staff.

6. Leadership Track

Junior staff seem to see the possibility of joining firm leadership as unlikely, or possible but not desirable. Senior staff, on the other hand, either say that it seems inevitable, or possible, but not desirable. It seems to me that neither junior or senior staff actually look forward to joining firm leadership, although some senior staff see it as their only option at some point.

8. Office Layout

Junior staff reported being satisfied, but having problems with lack of privacy and frequently moving. Senior staff reported different problems, and being dissatisfied with the space. These are not major disagreements, but I did notice that junior staff are more likely to complain about frequent desk moves.

9. Why do people leave?

The disagreements here have to do with the cited reason why people tend to leave a given firm. Both junior and senior staff generally offered the same two explanations – experience and compensation, but in many cases did not cite the same one. This is a minor area of disagreement, and it is perhaps best to say that experience and money are both major reasons why people finally decide to leave a firm.

11. What changes come with kids?

In this case, the junior staff generally have no children, and the senior staff do. The junior staff generally report that having children is not very impactful to work life, but senior staff report that this is not the case, desiring more flexibility and becoming more serious about compensation.

12. How many hours?

The clearest divide between junior and senior staff is the hours worked. In most cases, junior staff reported working reasonable hours, with senior staff routinely working 50-70.

# Motivational Profiles

In my reading about workplace dynamics, I came across a model for teamwork where members are motivated to join and maintain teams for some combination of four reasons7. These motivations are:

- Affiliation – having a social environment where needs such as praise or protection can be met.

- Power – the desire to control or effect others

- Affection – the desire to form positive emotional bonds

- Information – the desire to understand the context of their work: how to succeed, and where they stand relative to others.

These motivational profiles struck me as a good starting point to explain the reasons why people continue their careers in architecture (or don’t). However, architects and other people who identify as creative professionals have other desires which motivate their work. In order to better characterize the different ‘types’ of staff I developed the following core motivations, each giving and taking something unique from their workplace.

Autonomy

Someone motivated by autonomy is working to support a life outside work. For them, supporting their lifestyle or family is of primary importance. They may be likely to do the work which someone motivated by learning or self expression may avoid. Their greatest concern is compensation, and although they may be motivated to learn, it is with the goal of greater autonomy in the future, through licensure or other professional expertise.

The Work

Some days pass quickly as you are immersed in problem solving. When I say someone is motivated by the work itself, I refer to the satisfaction that comes from problem solving and task completion. These are not necessarily motivated by doing great design, but the opportunity to do the work efficiently. Many people motivated by task completion may flourish as project managers, but may not want to become a principal.

Camaraderie

These people enjoy being part of a team, developing deep relationships over the years. These people are concerned with their workplace’s social environment. The desire for social connection may be at odds with firms that assign break up and reassign teams frequently. These people may be happiest at a small firm.

Learning

Buildings are complicated, and to be an expert in buildings requires constant learning. Some people may pass over greater compensation for new and varied experiences. Some architects who are motivated strongly by the desire to learn may step out of the profession entirely, to stay in academia, or may prefer to work as a technical specialist.

Expression

This motivation is somewhat unique to creative work. The desire for personal expression is the the desire to leave a mark on our world, and to see your own ideas and tastes solidified in construction. Architects strongly motivated by expression may be willing to accept low pay to work for a famous designer. The desire for expression is often cited as a major reason to join the profession, but it also can be a cause of great frustration.

# Recommendations for Firms and Individuals

For architects looking for the right firm, my recommendation is to read the motivational profiles I have outlined and try to discern which of them apply to you personally, and which is most important. What is most important to you – making money right now? Gaining experience? Having opportunities to learn? Being as specific as possible will help you figure out which firms would suit you and which would not.

After you have a better idea of what you want, you need to figure out which firms offer it. All firms want to create the impression that they are good places to work, but in reality they are only good places to work for certain people. Read over the questions I developed, and develop your own surrounding the issues that you care most about.

For managers trying to find the right staff, rather than simply trying to see if a potential hire is ‘a good fit’ and capable of fulfilling job responsibilities, try to see if they are likely to have the right motivational profile for the position in question. Some positions offer very little opportunity to learn, and some offer much. Some positions pay poorly but are still desirable. By being specific about how the job is satisfying and how it may be unsatisfying, you have a better chance of finding the right person.

At times, the hiring process, from both sides of the table, can seem like an exercise in deception. Firms will paint a rosy picture about the nature of the work and the opportunities it comes with, and applicants will paint a rosy picture of their work ethic and loyalty. I do not believe this has to be the case. I think that by asking better questions about our needs, we can replace this deception with a shared understanding of what we need to be happy and productive.

# Further Information

You can download the entire thesis book here.

- “A Majority of Architecture Firms are Considering Mergers and Acquisitions.”

Architect. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 May 2017. - Cuff, Dana. Architecture the Story of Practice

Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992. Print. - Dorsey, Robert W. Project Delivery Systems for Building Construction

Alexandria, VA: Associated General Contractors of America, 1997. Print. - “Firm Survey Report: The Business of Architecture 2016.”

Aia.org. American Institute of Architects, n.d. - Kostof, Spiro, and Dana Cuff. The Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession. Berkeley: U of California Press, 2008. Print.

- Sedorkin, Gail. Interviewing: a guide for journalists and writers.

Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2011. Print. - Stewart, Greg L., Charles C. Manz, and Henry P. Sims. Team Work and Group Dynamics. New York: J. Wiley & Sons, 1999. Print.

- Suh, Michael. “Questionnaire design.” Pew Research Center. N.p., 29 Jan. 2015.